This article was originally posted on IFPRI's Insights website.

Can insurance help Ethiopian farmers survive the droughts that are likely to  come?

come?

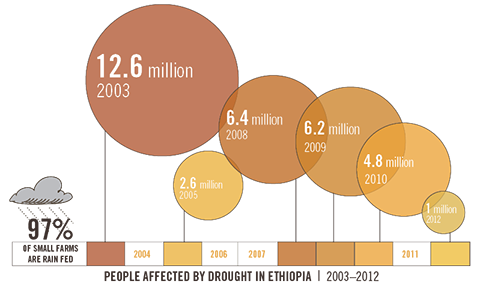

Recently, scientists uncovered the inconvenient truth that drought in eastern Africa is likely here to stay. They placed the blame squarely on climate change—namely, on the linkage between the warming Indian Ocean and decreased rainfall over the Horn of Africa. Given the ubiquity of drought in the region, how can farmers cope?

“Unexpected events and shocks are very prevalent in rural Ethiopia and really matter for household welfare today and into the future,” explains Ruth Hill, until recently a senior research fellow at IFPRI. “The main risk is drought. Households have a limited ability to manage it.” While various types of conventional agricultural insurance exist, they have been poorly suited to smallholder farmers and too expensive for them. In their January 2013 research note, Insuring against the Weather, IFPRI researchers studied the best mechanisms for providing index-based weather insurance to farmers in the Oromia region of Ethiopia.

No cushion

In Ethiopia, more than 80 percent of the population is involved in the agricultural sector and 97 percent of small farms are rain fed. For these farmers, rainfall determines not just their seasonal harvest but the well-being of their families for years to come. When drought strikes, many smallholders lack enough cash or savings to absorb the shock. A crop failure can lead families to sell off productive assets such as livestock, entrenching them in a cycle of poverty. What’s more, without a cushion to cope with weather risks, smallholders may be reluctant to make the productivity-enhancing investments that can shift farms beyond mere subsistence. Ethiopia’s flagship social security concept, the Productive Safety Net Programme, has helped protect households from slipping into post-shock poverty. But what was lacking, until about five years ago, was an insurance product designed specifically to meet the needs of Ethiopia’s small-scale farmers.

IFPRI’s approach to insuring these farmers married tradition with innovation, combining customary Ethiopian social structures with an index insurance scheme supported by a private sector insurance company (the Oromia Insurance Company) and a microfinance institution (Buusaa Gonofaa).

Tradition meets innovation

Ethiopian self-help groups known as iddirs began as informal burial societies to which heads of household paid monthly dues to help cover the cost of family funerals. In recent years they have evolved to provide a more diversified portfolio of support to members, serving as a way of saving for wedding, health, and home expenses as well as providing livestock insurance. According to Hill, “The idea of equality is in everything these groups do. Everyone pays the same amount and receives the same amount.”

Building on this community-based risk-sharing approach, researchers conceptualized insurance products for selected villages in the Oromia region, to be provided through iddirs. They offered two index-based weather insurance policies for each month of the May–September rainy season, based on historical rainfall data and paying out when rainfall fell short of a certain threshold.

One reason index-based insurance schemes have enjoyed success with smallholders is that there is no need to file and corroborate individual claims. All farmers are compensated equally for a weather event (or lack thereof), lowering operating costs and the price the farmers must pay for the policy. Payouts are received much more rapidly than with traditional insurance, and the process is transparent because payout decisions are based on localized weather data. Collaborating with trusted microfinance institutions already working in rural areas, the project brought in urban area-based insurance companies that would have otherwise found it too costly to serve these populations. “That model—a microfinance institution plus an insurance company—seems to be the one that works,” explains Hill.

“What about your kids?”

Convincing farmers to adopt the concept was no easy task, however. Insurance can be a hard sell—by its very nature, it’s a roll of the dice. “These are poor people, and we are asking them to pay money ahead of time in the hope they will get it back someday if something bad happens. This needs a lot of trust,” says Hill. Some farmers initially wanted the product for free, recalls IFPRI Research Fellow Guush Berhane. “I dropped all my academic jargon,” he says. “I said, ‘At some point you must walk on your own two feet. What about your kids? Should they continue waiting for emergency aid?’ So they said, ‘Yes, we have to do something now.’”

There was another, even stronger argument though. Researchers discovered that “nothing sells insurance like insurance payouts.” The farmers who purchased insurance through the iddirs were likely to know of a household that had received a payout. The involvement of the iddirs reduced the risk of purchasing insurance for individual households, built resiliency during periods of shock, and helped build trust around the concept of index insurance.

Prospects for expanding the program are promising, too. “We could link the iddirs in the north and south so they can help each other. Imagine bringing them together to create a larger insurance company. Ethiopia is diverse, so that helps spread risk,” says Berhane.

Perhaps the fundamental lesson lies in the foundation of the project, which built upon existing roots and systems to better meet the needs of farmers. Hill explains, “It requires a lot of discussion with farmers first: crops, rain, what is good, what is bad? We didn’t design it first; we started with the farmers.”

For more information on this topic:

Insuring Against the Weather, by G. Berhane, D. Clarke, S. Dercon, R. V. Hill, A. S. Taffesse, ESSP Research Note, January 2013