Index insurance is a relatively new business area for Ethiopia, and which continues to generate much discussion on how insurance products can fit into the lives of rural communities. Farmers simply need to know that if they have a loss, will they get paid.

Agriculture and livestock are the key sources of income for most rural households in Ethiopia, and therefore, if crops fail or livestock die due to environmental factors or otherwise, this greatly impacts these communities.

For such agricultural households, increasing productivity using fertilizer or improved seeds is an effective way to intensify yields. However, the take-up rate of fertilizer and improved seeds in Ethiopia is still low, one major reason being the income risks faced by farmers. Similarly, pastoralist households may be reluctant to invest in improved breeds for fear of drought risk that can decimate herds.

Policies and products that help the farmers and pastoralists mitigate or manage these risks should contribute towards increasing productivity. One way to address risk is through the use of insurance, such as weather or forage index insurance. If this kind of insurance protection can reliably unlock demand for risky but productivity-enhancing investments, then it holds real promise to bring improvements in income for poor and risk-prone agricultural communities.

A variety of efforts introducing index insurance in Ethiopia have been implemented in the past few years. Several of these innovative projects are particularly promising, and deserve closer examination.

A workshop on the theme of Index Insurance was held on 3 December 2015 in Addis Ababa to share and examine research activities undertaken in Ethiopia within this sector. Hosted by ESSP, along with partners – ILRI and BASIS, it provided a forum to consider many aspects of insurance, including:

• Index insurance pilots in both the agricultural and livestock sectors

• Approaches for reaching out to farmers and pastoralists, including linking informal and formal insurance mechanisms

• Scaling up index insurance projects

• The role of public support for index insurance

• The potential role of public and private insurance and financial sectors

Thus follows a brief review of contributions made throughout the event.

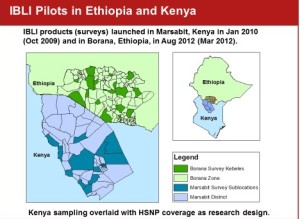

Christopher Barrett from Cornell University described the Index-Based Livestock Insurance (IBLI), both from the research perspective and how to make the index suitable in practical terms. The index is based on average losses in a community and not for individual losses, the principle being that if gains fall below a certain threshold, payment is received. The key determinants for farmers are: price (based on how well the policy is designed) and education (to establish effective demand), along with liquidity (how much cash in hand a farmer has) and the size of herds (when dealing with livestock). Overall, Christopher Barrett expressed that the research shows that people are generally better off with IBLI coverage, significantly decreasing the likelihood of distress sales and missed meals. For further details see his presentation.

Figure 1 – IBLI Pilots in Ethiopia and Kenya

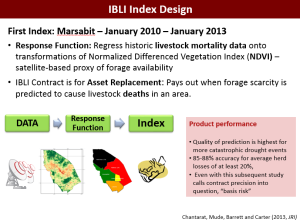

Insurance take up is generally disappointingly low. Hence, tackling the barriers, such as index design, policy and institutional infrastructure, and establishing effective demand, these all impact scaling up, as described by ILRI’s Andrew Mude. The difficulty arises when trying to develop indexes from often poor data. However, with the use of remote sensing techniques to help in an asset protection program and quality data, along with geographic and temporal coverage, pricing and fitting index to the risk, this moves towards creating a solution to move up to scale.

Figure 2 – IBLI Index Design

From a different perspective during the workshop, Tesfaye Desta from Oromia Insurance described the challenges to increase purchases of insurance products, having implemented a pilot. He remains optimistic that in time, reaching out to customers will reap benefits. Solomon Zegeye from Nyala Insurance reflected on the involvement of Dashen Bank and other partners to help farmers finance the often high insurance premiums. He described EPIICA – an innovative project that aims to give insurance and credit to farmers. Many challenges are identified, but Zegeye clearly expressed a way forward focusing on building capacity, addressing regulatory issues, and working in collaboration and committing to succeed.

A number of speakers during the workshop commented on the difficulty at getting banks or other private sector organizations involved in insurance in Ethiopia because of the risks involved. If this risk, or basis risk, is reduced so that the probability of farmers not being paid when they should have been paid is shrunk, this would go a long way to encourage farmers of the value of insurance to protect their assets.

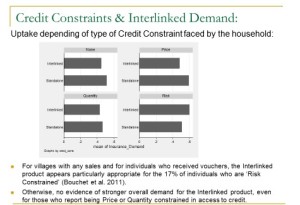

Another angle on index insurance was explored by Craig McIntosh from University of California on weather index insurance, where rainfall is used as the measure for creating the index. The research highlighted the importance of credit availability with insurance uptake, and notably, those kebeles covered by the PSNP, people were less willing to fund insurance themselves.

Figure 3 – Credit Constraints and Interlinked Demand

As pointed out by Michael Carter from the University of California, we know everything about risk, but what can index insurance do? Carter shared thoughts about some of the already mentioned challenges, but voiced the question “can we make a more stable situation for the poor by reducing vulnerability and incentive investments?” In his research, Carter used satellite information to help predict yields, but then followed this by testing the data on the ground through audits. One of the key factors in taking up insurance is trust, so demonstrating ground truth in this way was shown to give greater confidence to farmers. Bad data is often the reason for high premiums, so if this could be addressed, it would make a significant difference.

Weather-index insurance was investigated further from the perspective of informal (through “iddirs”) and formal insurance in the Ethiopian setting. Guush Berhane expressed that demand was disappointingly low for reasons largely resulting from basis risk, trust and high transaction costs. In research undertaken two years ago, the focus was to mitigate basis risk through “gap insurance” (see ESSP Outcome Note 04). There appears huge variation in interest across the country, however, the risk sharing element introduced through local community “iddirs” seems to instill trust that emergencies can be tackled more effectively. IFPRI worked with Buusaa Gonofaa – micro-finance institution – in this research as they covered many regions. Teshome Dayesso (CEO, Buusaa Gonofaa) described how they created policies that matched requirements. Although the pilot was successful in the uptake of insurance, those involved in the pilot considered how this could be successfully scaled up. In his final comments, Teshome Dayesso proposed the collaboration with cooperatives or with other partners as a means of going forward.

Figure 4: Poster to illustrate the gap insurance among farmers

Finally, the workshop touched on how agricultural insurance is coping in the face of increased climate instability. Lena Heron from USAID described that we are working towards the approach to improve the nimbleness of humanitarian responses, improvements to markets, and water and resource management in general. Heron expressed that some improvements in resilience were being observed, but El Niňo related droughts have been very difficult to absorb such shocks by such designs. Therefore, seeking to transfer the “shock” out of the system with insurance instruments that tackle resilience, is the challenge we face.

Michael Carter reviewed models that consider variables that influence people’s ability to manage their vulnerability, but then by adding climate change to the mix totally alters the picture. In his final session, Carter revisited integrating social protection and the government’s involvement to help keep any kind of insurance program in the reach of the most vulnerable, considering “risk pricing in the face of uncertainty” (see Carter’s presentation).

There is no conclusive answer on how to drive insurance uptake in Ethiopia. However, from the quality research, collaborative working with financial and legal systems, better understanding of the nature of risks farmers face, investing in data and other local infrastructures, improving local capabilities in designing insurance products, consumer education, building trust with the farmers, and improvements in regulations, are among those elements that will move the agricultural index insurance industry to scale.

To download any of the conference presentations, visit Slideshare.

Here are some of ESSP’s published works:

• The impact of research on weather index insurance (Outcome Note 04)

• Weather-based insurance for African farmers has issues (SciDevNet Article)

• Insuring against the weather (ESSP Research Note number 20)

• Saving for a Sunny Day (IFPRI Insights Magazine)

• Diagnostic Study of Providing Micro-Insurance Services to Low-Income Households in Ethiopia (ESSP-EDRI Report)

• Adoption of Weather Index Insurance. Learning from Willingness to Pay among a Panel of Households in Rural Ethiopia (ESSP Working Paper 27)

Visit our website for more information.